Retinitis pigmentosa is a disease of the retina that causes progressive loss of vision, leading to blindness. Learn about your symptoms and new research underway to improve your treatment.

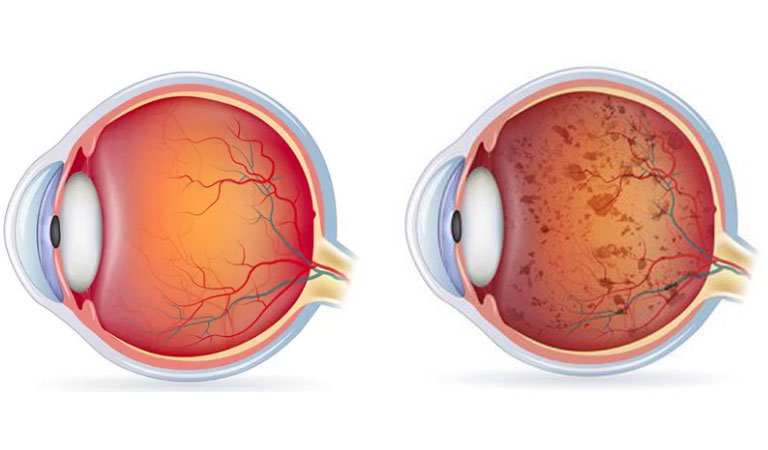

The retinitis pigmentosa is not a single disease, but a group of degenerative diseases affecting the eye and typically produce a slow, progressive loss of vision. The part of the eyeball most affected is the retina, which is the layer that covers the inner part of the eye and is responsible for acquiring and processing images from the outside, converting them into nerve impulses, and sending these to the brain through the optic nerve.

Generally, the involvement is bilateral, so both eyes are affected. The most common symptoms are night blindness, limited field of vision with loss of peripheral (side) vision, and glare. Over time, blindness can occur.

Retinitis pigmentosa can appear as an isolated disease (non-syndromic retinitis pigmentosa) or be associated with other ocular or systemic pathologies (syndromic retinitis pigmentosa). In this way, people with retinitis pigmentosa can present other vision alterations such as myopia, astigmatism, cataracts, glaucoma, or cornea changes.

In addition, and although they are rare (they represent approximately 15% of all cases), retinitis pigmentosa can be associated with syndromes that also affect other parts of the body. The most frequent are degenerative diseases of the central nervous system (made up of the brain and spinal cord), muscles, and metabolic disorders. One of the most frequent associations is the so-called Usher syndrome. Retinitis pigmentosa is linked to deafness, and Bardet-Biedl syndrome, where it appears associated with obesity, low IQ, more than five fingers (polydactyly), and small genitalia ( hypogonadism ).

Epidemiology of retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is the most common cause of hereditary degeneration of the retina and the most common cause of blindness of genetic origin in adults. It is estimated that it affects one in 3,700 people, so that around the world, there are about 1.5 million people with this disorder. In Spain, more than 15,000 people suffer from this ocular pathology, and it is estimated that some 500,000 people are carriers of the altered genes and, therefore, potential transmitters of the disease.

It is slightly more common in men (around 60% of those affected are men), and there seem to be no differences between races. Although it is a disease present at birth, it is rare to manifest itself before adolescence, making it slowly and progressively. It is not usually discovered until it is pretty advanced.

Causes of retinitis pigmentosa

It is considered that retinitis pigmentosa is a disease gene and therefore is not caused by infection, trauma, injury, or another external agent. These genetic alterations cause the cells of the retina called photoreceptors (rods and cones) to function incorrectly, in such a way that over time many of them degenerate and die, thus producing a progressive loss of vision. Other theories suggest that this disease has an autoimmune, biochemical, or metabolic cause; however, there is insufficient evidence to prove it.

Retinitis pigmentosa can appear sporadically (in these sporadic cases due to new mutations, affected people do not transmit the disease to their offspring) or be hereditary (being hereditary, it usually affects other members of the same family ). Therefore, if a person is diagnosed with this disease, it is recommended that an ophthalmologist evaluate family members.

- Autosomal dominant (one of the parents is affected and transmits the disease to half of their children): these are usually the minor, severe forms since the disease usually progresses very slowly and the patient maintains good central vision until advanced age. It affects both men and women.

- Autosomal recessive (the parents do not suffer from the disease but are carriers of it, in such a way that 25% of the offspring may be affected): it is the most common inheritance pattern. Retinitis pigmentosa transmitted in an autosomal recessive form is more severe than the previous ones and can cause symptoms in adolescence (mainly dark adaptation problems).